Table of Contents

Introduction

Say the names Taylor Swift, Lionel Messi, or even political figures like Donald Trump and Joe Biden, and a flicker of recognition lights up in most eyes. Venture into the realm of economics with Janet Yellen and Jerome Powell, and that flicker might dim, reserved for the more financially attuned among us. But there’s one name, pivotal yet less chanted in mainstream corridors, that has sculpted the very bedrock of our economic world: John Maynard Keynes.

A titan in the annals of economics, Keynes is a figure whose influence ripples through our daily lives, often unbeknownst to us. Some herald him as a visionary, others critique the world he helped mold, but few can deny the indelible imprint of his legacy on modern macroeconomics.

For those unacquainted with the man behind Keynesian economics, or for those who only know the term in passing, this exploration offers a window into the life and impact of the man who, arguably, has had a greater sway over our economic landscape than many contemporary political figures.

John Maynard Keynes: A Villain’s Origin Story

John Maynard Keynes, the architect of modern macroeconomics, was born into the intellectual embrace of Cambridge, England, on June 5, 1883. His life began in the hallways of academia, with a father, John Neville Keynes, who was not just an economist and a University of Cambridge lecturer but also a philosopher of sorts, delving into the art and norms of economics.

His mother, Florence Ada Keynes, wasn’t just the matriarch of the household; she was a social reformer, a pioneer in her own right as Cambridge’s first female councilor and later its second female mayor. Her legacy was one of compassion and change, marked by her relentless efforts to provide pensions for impoverished elderly and reintegrate workhouse inmates into society.

According to the economic historian and biographer Robert Skidelsky, Keynes’s parents were loving and attentive. Keynes received considerable support from his father, including expert coaching to help him pass his scholarship exams and financial help both as a young man and when his assets were nearly wiped out at the onset of Great Depression in 1929. Keynes’s mother made her children’s interests her own; these included her charitable works.

In this intellectually fertile ground, young Keynes wasn’t just raised; he was sculpted, with every familial conversation possibly doubling as a lecture in economics or a lesson in social justice. His education was a testament to his family’s standing – a King’s Scholarship to Eton College and a subsequent passage to King’s College, Cambridge.

At Eton, he was amidst future leaders, his peers being the offspring of Britain’s most influential. At Cambridge, his mathematical prowess was redirected to economics by Alfred Marshall, a giant in the field. Here, Keynes also found his social niche with the Bloomsbury Group, a cohort of thinkers and artists who prided themselves on their avant-garde approach to life and learning. This milieu, with its heady mix of economics, liberal thought, and artistic freedom, was the crucible in which Keynes’s groundbreaking ideas were forged.

The Sins Of The Father

The elder Keynes, a figure as foundational as the red bricks of Cambridge he roamed, carved a niche in the annals of economic thought, not merely by teaching but by dissecting the very essence of economics into three distinct realms. His tripartite division – positive, normative, and the ‘art’ of economics – was like setting the stage for a grand theater of fiscal understanding.

In his vision, ‘positive economy‘ was the unvarnished truth of economic landscapes, a raw, unembellished snapshot of ‘what is’. It’s the bare bones, the skeletal structure upon which the flesh of economic theories would be layered. Then, there was ‘normative economy‘, the moral compass, the realm of ‘what should be’. Here, economics transcended the cold hard data, intertwining with ethics, nudging the numbers towards idealism.

And finally, the pièce de résistance, the ‘art of economics‘. This was where the elder Keynes bridled the untamed horse of economic theory and rode it into the sunset of real-world application. He saw it as a bridge between the theoretical isles of positive and normative economics, a translator fluent in both the language of idealism and practicality. In this triad, John Neville Keynes laid the groundwork, perhaps unknowingly, for his son’s later foray into a world where economics was not just a science, but an art, a philosophy, and a guiding light for nations.

The Making of an Economic Antagonist: Keynes’s Early Years

Keynes’s stint with the British government during the tumultuous times of World War I wasn’t just a line on his resume; it was a crucible that shaped his economic vision. His role at the 1919 Versailles Peace Conference, as a representative of the British Treasury, was more than just a job. It was a front-row seat to the geopolitical maneuverings that would redraw the maps and economies of Europe.

Picture Keynes, a young economist amidst the grand halls and heavy curtains of Versailles, where the air was thick with cigar smoke and the burden of post-war decisions. His task was to lend his economic expertise to the British delegation, but what he encountered there was a reality that clashed with his principles. The reparations imposed on Germany, he believed, were not just harsh but a recipe for future disaster. The seeds of dissent germinated in Keynes’s mind, eventually leading him to resign in a blend of frustration and foreboding.

This episode at Versailles wasn’t just a career move; it was a pivot point that turned Keynes towards a path of vocal criticism and alternative thinking. His subsequent book, “The Economic Consequences of the Peace,” wasn’t merely an academic critique; it was a siren call, warning of the dire economic fallout of the Treaty of Versailles. Keynes didn’t just write a book; he lit a beacon that would cast long shadows over the economic landscapes of Europe.

Fast forward to the Great Depression, and we find Keynes again, this time grappling with personal financial turmoil. His experiences in the stock market during this period were not just about numbers on a ledger; they were lessons etched in the harsh realities of economic downturns. The support he received from his father during these times was more than financial aid; it was a lifeline that perhaps deepened Keynes’s understanding of the vulnerabilities and vicissitudes of economies.

Then came “The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money” in 1936, a tome that was less a book and more a manifesto challenging the bedrock of classical economics. Writing in the shadow of the Great Depression, Keynes wasn’t just penning theories; he was architecting a new economic paradigm. His critique of classical economics wasn’t just academic rebellion; it was a clarion call for a new approach to dealing with unemployment and deflation.

Keynes crafted new economic lexicon: from the consumption function (relationship between income and spending) to the multiplier effect (increased spending increases GDP), he forged a new path forward in the world of macroeconomics. Keynes’s concept of aggregate demand was not merely an economic term; it was a new lens through which to view the workings of an economy in distress. His advocacy for government intervention through fiscal policy wasn’t just a theoretical construct; it was a bold, almost revolutionary call to action for governments to step in and steer economies away from the abyss.

In the grand scheme of economic history, Keynes’s early years were more than just a prelude to his later fame. They were the formative chapters in the story of a man who would become both a hero and a villain in the annals of economic thought, a man whose ideas would shape policies, inflame debates, and leave an indelible mark on the world. This was the making of John Maynard Keynes, an economic antagonist to some, a visionary to others, but undeniably a pivotal character in the narrative of modern economics.

The Rise of Keynesian Economics

In the 1930s, the stage of economics was set with classical theories that had long reigned supreme. These theories, like actors of an old play, held certain core beliefs:

- Self-Regulating Markets: The classical economists were like steadfast captains, believing in the ship of the market to navigate and correct its course naturally, ensuring efficiency and full employment.

- Say’s Law: This was akin to an economic mantra stating that production inherently creates enough income to buy all it produces, a self-fulfilling cycle of supply and demand.

- Laissez-Faire: Here, the government was seen as a hands-off overseer, allowing the economic garden to grow untended, believing in the natural order to bring balance and prosperity.

- Flexible Prices and Wages: The idea here was that prices and wages were like water, finding their level, adjusting fluidly to the ebbs and flows of supply and demand.

- Loanable Funds Theory: This theory painted interest rates as a dance between the savings available for lending and the demand for these funds, a delicate balance determining the cost of borrowing.

Enter John Maynard Keynes, the intellectual maverick who would turn these ideas on their head with “The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money.” His ideas were audacious daubs of paint on the classical canvas:

- Active Government Role: Keynes argued for the government to be not just a spectator but an active player in the economic arena, especially during downturns, using fiscal policies as tools to manage economic cycles.

- Demand-Driven Economy: He shifted focus to aggregate demand, viewing it as the engine driving economic activity. In his narrative, inadequate demand could lead to a prolonged unemployment tragedy.

- Sticky Prices and Wages: Contrasting the classical view, Keynes saw prices and wages as stubborn actors, resistant to downward movement, thus preventing market self-correction.

- Liquidity Preference Theory: Here, Keynes introduced a new character in the interest rate story, suggesting that the rate is influenced by people’s preference for liquidity and the money supply controlled by central banks.

- Multiplier Effect: Keynes introduced this concept as a narrative twist, suggesting that government spending could have a greater impact on national income and consumption than the initial expenditure.

Keynes’s economic stage was one where government intervention was not just necessary but vital for the health of the economy, especially in times of downturns. His theories, forming the bedrock of what we now call Keynesian economics, emphasized the need for proactive government policies to stabilize economies.

This divergence from classical economics was not just a theoretical debate; it was a fundamental shift in how nations approached fiscal policy. Keynes’s influence extended beyond the academic realms into the halls of power, reshaping economic policy and laying the groundwork for the economic structures that emerged post-World War II. His role in shaping the Bretton Woods Conference, leading to the creation of the IMF and the World Bank, was a testament to his profound influence on the global economic landscape.

The Great Battle of Bretton Woods: Keynes’s Clash of Titans

In July 1944, as World War II’s echoes still reverberated, a gathering of economic minds converged in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. Among them was John Maynard Keynes steering the British delegation with a blend of vision and pragmatism. This wasn’t just a conference; it was a battleground for the future of global finance, and Keynes was ready to leave his mark.

Keynes, a maestro of economic theory, championed international cooperation like a modern-day Prometheus, seeking to light a path away from future financial infernos. His brainchild, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), emerged from the ashes of Bretton Woods, destined to stabilize currencies and cushion nations against the shocks of economic crises. Alongside, the World Bank took its first breath, poised to rebuild war-ravaged Europe and later, to shepherd development projects across the globe.

Yet, not all of Keynes’s visionary ideas saw the light of day. His ambitious plan for an International Clearing Union, coupled with a novel reserve currency named “Bancor,” (this is real my fellow Mandibles enthusiasts) faced a formidable adversary: American opposition. The United States, flexing its economic muscles, was not ready to dance to Keynes’s tune, favoring a world where the U.S. dollar, tethered to gold, reigned supreme. Keynes’s dream of a more equitable financial realm, where the dollar did not overshadow the stage, was left unfulfilled.

Thus, the Bretton Woods Conference, with Keynes as one of its master architects, carved the contours of our present-day international monetary system. Although Keynes’s vision was not fully realized, his influence shaped the economic landscape we navigate today. His legacy extends to global institutions that, despite not being directly elected, significantly impact the lives of people worldwide. In the grand chessboard of global finance, Keynes’s strategies at Bretton Woods were both a triumph and a testament to the complex interplay of international diplomacy and economic strategy.

Keynesian Economics in Practice: A Bittersweet Symphony of Theory and Reality

In the sweeping narrative of modern economics, the legacy of John Maynard Keynes looms large, his theories carving indelible marks on global financial landscapes. Post-1944, his economic philosophy not only shaped policy but also orchestrated the rhythm of entire economies.

Global Influence Post-World War II: The Keynesian Crescendo

In the years following World War II, Keynesian economics became the conductor’s baton orchestrating economic policies worldwide. The post-war era, often hailed as the “Golden Age of Capitalism,” witnessed nations embracing Keynesian strategies with gusto.

Governments boldly stepped in, wielding fiscal policies as tools to stabilize economies, stimulate growth, and chase the elusive dream of full employment. For instance, the U.S. implemented the Interstate Highway System, enhancing trade and transportation. Furthermore, the era saw a reduction in financial crises and inequality, with progressive taxation playing a crucial role in wealth redistribution.

This period was marked by an unprecedented economic boom, a testament to the Keynesian belief in proactive government intervention. Despite its successes, the Keynesian approach faced challenges during the stagflation of the 1970s, prompting a shift towards other economic policies in subsequent decades.

Stagflation: A Discord in the Keynesian Symphony

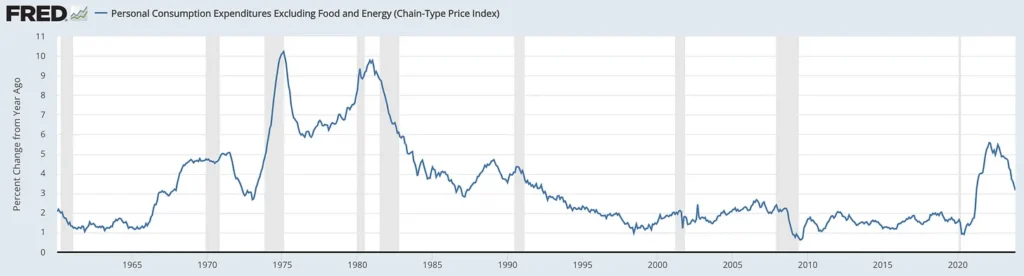

However, the Keynesian symphony faced dissonance in the 1970s with the onset of stagflation – a bewildering combination of high inflation and stagnant economic growth. Inflation broke above 10% in 1975 and unemployment was at 8.2% the same year.

The US government also implemented fiscal policies to stimulate economic growth and reduce unemployment. This included increasing government spending for defense (Vietnam War) and cutting taxes on small businesses, individuals and eventually corporations (and increased standard deductions) to boost aggregate demand.

Between 1971 and 1974, the Nixon administration introduced wage and price controls to save citizens from price gougers (sound familiar?). These controls temporarily slowed the rise in prices but led to exacerbating shortages, particularly for food and energy.

This phenomenon presented a formidable challenge to Keynesian theories, which seemed ill-equipped to address simultaneous inflation and unemployment. The stagflation crisis spurred a reevaluation of economic policies, leading to a gradual shift towards alternative economic schools of thought in the following decades.

One such theory was Neo-Keynesianism, which differentiated between demand-pull and cost-push inflation. Neo-Keynesianism acknowledged that monetary and fiscal policies were less effective against aggregate supply fluctuations, such as the oil price shocks during this period.

The Great Financial Crisis: 2007-2009

The Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2009 is a modern example of Keynesian principles in action. In response to the financial meltdown, the U.S. government implemented a massive stimulus packages. The Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) in 2008 authorized the expenditure of approximately $700 billion to purchase distressed assets, particularly mortgage-backed securities, and provide capital injections to banks.

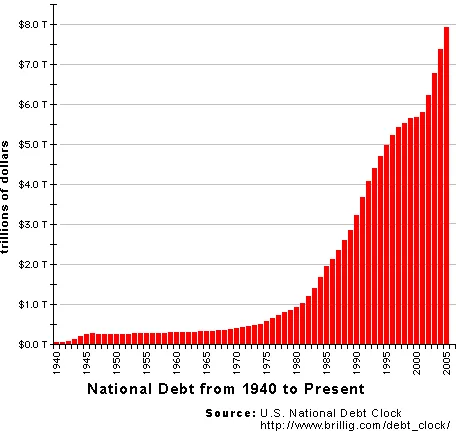

This intervention was aimed at stabilizing the financial system and preventing a more severe economic collapse. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, amounting to about $831 billion, aimed to save and create jobs, spur economic activity, and invest in long-term growth. Despite these measures providing short-term economic relief, they reignited debates about the long-term implications of such significant government intervention, including substantial increases in national debt, which has grown from $9 trillion in 2007 to $34 trillion today.

The Enduring Impact on Economic Policies and Thought

Keynesian economics, despite its ebb and flow in popularity, has left an indelible mark on the canvas of global economic policy. Its core principles – emphasizing the need for government intervention during economic downturns and using fiscal policy as a lever to manage economic cycles – have become integral components of economic strategy across nations even today. Governments worldwide have repeatedly turned to Keynesian tactics, especially in times of financial turmoil, to stimulate their economies and mitigate the impacts of recessions.

However it is important to recognize that the Keynesian approach often leads to increased government spending, which has, over time, contributed to soaring national debt levels. The image below shows how steadily US Government debt has increased since the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1944 (I had to cut it off before the Great Financial Crisis otherwise the rise in debt from 1945-1970 would not be noticeable). This raises critical questions about the long-term fiscal sustainability and the economic burden passed onto future generations.

The Keynesian endorsement of government intervention in market dynamics has sparked debates about its potential infringement on free-market principles and individual freedoms. Critics argue that excessive government involvement could stifle innovation and efficiency, while proponents see it as a necessary measure for the greater economic good, especially during crises.

The Avengers: Austrian Economics and Free Market Capitalism

While Keynesianism reigned supreme in the mid-20th century, it was not without its challengers. Austrian Economics and Free Market Capitalism emerged as formidable opponents, advocating for a vastly different economic approach. Let’s delve into these alternative schools of thought and their critiques of Keynesian principles.

In the grand economic narrative, Austrian Economics and Free Market Capitalism emerge as the Avengers against Keynesian philosophy. Austrian Economics, birthed by Carl Menger and later championed by Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises, emphasizes individual choice and subjective value. It’s a world where complex market phenomena are the sum of individual actions, not aggregate movements.

Free Market Capitalism, with its roots deep in voluntary exchange and minimal government touch, celebrates the sanctity of private property and competitive markets. Its proponents herald it as the pinnacle of efficiency and innovation, fostering growth and consumer choice.

Austrian Economics and Free Market Capitalism stand in stark contrast to Keynesianism. Where Keynes advocated for government intervention, Austrian economists like Hayek emphasized the dangers of such interference, arguing it disrupts the natural order of the market.

They championed the power of individual decision-making, positing that those closest to economic activity – not government planners – are best suited to drive growth and innovation. In their eyes, spontaneous order and minimal state interference are key to economic stability and growth. Free Market Capitalism echoes this, advocating for the invisible hand of the market over the visible hand of the state.

These ideologies, however, are not without criticism. While Austrian Economics is lauded for championing democratic values and exposing government failures, it faces scrutiny for its lack of empirical rigor. Free Market Capitalism, while driving competition and innovation, is often blamed for societal inequalities and unchecked environmental damage.

Globally, places like Hong Kong, Singapore, and Switzerland reflect these principles, albeit with nuances like government-run housing programs in Singapore or Switzerland’s liberal economic policies.

In essence, Austrian Economics and Free Market Capitalism offer a staunch rebuttal to Keynesianism. They underscore the power of individual choice and market forces, yet their implementation reveals a complex tapestry of benefits and challenges, from fostering innovation to grappling with social and environmental concerns.

Never forget the words of present-day Austrian Economists Stephan Livera: “Those closest to the money printer stand to gain the most.” And I will add one small piece: those furthest from the money printer are incentivized to find an alternative to our current monetary system: Bitcoin.