This article was originally published by Emile Phaneuf on Medium.com

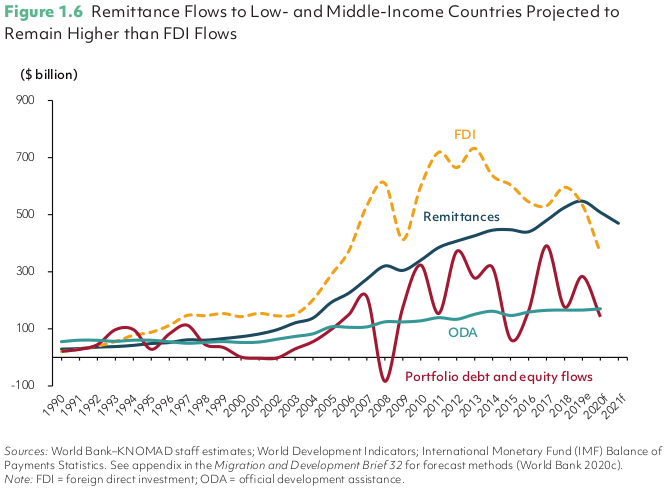

Remittances are an under-recognized but vital part of the global economy. The classic scenario is one in which economic migrants in one country send money back to friends and family in their country of origin. The transaction sizes are often relatively small (usually between $200 to $300 every month or two). But despite relatively small average amounts per transaction, global remittances (quite impressively) remain comparable to (and surpass) global Foreign Direct Investment (FDI).

As of the time of this writing, the World Bank lists eleven countries for which personal remittances amount to over 20% of GDP, with Tonga in the lead. In terms of total remittance volume received, India tops the list (by far).

Costs for traditional remittances

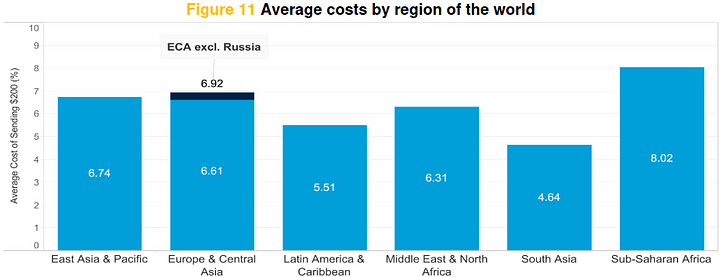

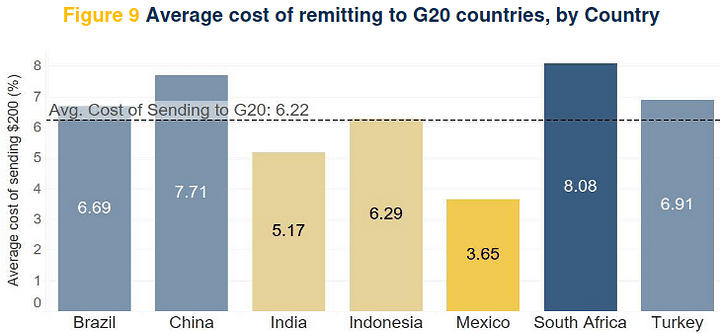

According to World Bank estimates, the average global cost of remitting $200 through a Money Transfer Operator (MTO) such as Western Union and MoneyGram has fallen year on year but still remains well over 6%. Sub-Saharan Africa as a region pays the highest average cost worldwide.

Dilip Ratha, Head of KNOMAD and Lead Economist for Migrations and Remittances for the World Bank makes a humanitarian case for bringing down remittance costs for the world’s poor. He cites anti-money laundering laws (AML) as one of the primary challenges to this goal. In his own words, “…faster, cheaper, better [remittance] options can’t be applied internationally because of the fear of money laundering, even though there is little data to support any significant connection between money laundering and these small remittance transactions.”

So where will innovation come from?

Blockchain remittance solutions have been recognized by both the World Economic Forum and the European Union, and thus far, there seems to be at least four different models with which companies in the Blockchain and cryptocurrency space have attempted to solve the cost problem. I will briefly discuss each of them here. As we will see, some are more promising than others.

Model 1. Use of Bitcoin (without the Lightening Network) as “rails”

The first model involves using Bitcoin as “rails.” At least one company, Rebit.ph, attempted this model as far back as 2014 — before the Lightning Network white paper was even published. This use of Bitcoin created a bit of “this changes everything” hype but ultimately failed.

Rebit.ph sought to make Bitcoin remittance (“rebittance”) work for the Philippines, where the last leg of money transfers tended to be with pawn shops on the receiving end. A former employee of Rebit.ph estimates that to send $10, there was a charge by the pawn shop networks of roughly 6–7%. The same employee wrote in a Medium article that “[because] we were mimicking the traditional remittance process so closely, we were also mimicking its costs.”

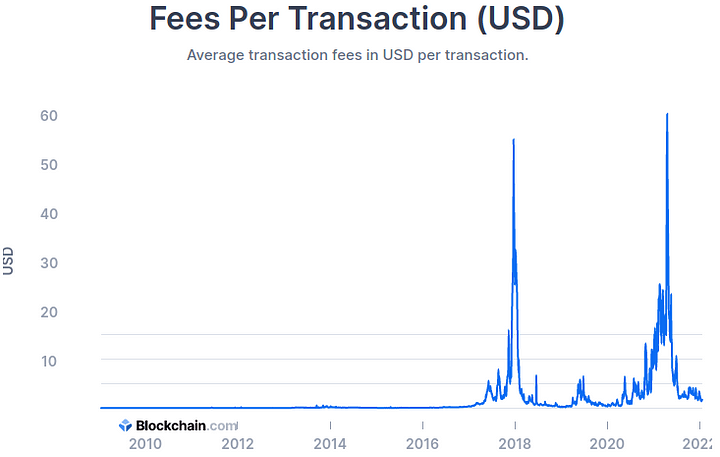

Even without such fees charged by pawn shops or other financial service providers, perhaps the more important reason this model would be unfeasible today is that the transactions happened on-chain (layer 1). It would be doubtful that any company today operating under this model would be capable of bringing remittance costs down low enough to be attractive when compared to traditional remittance services such as Western Union, MoneyGram, and WorldRemit.

An on-chain (layer 1) Bitcoin remittance model may have sounded like a great idea back in 2014 when transaction fees were low. But such an idea today would be silly to propose without use of side chain (layer 2) solutions such as Lightning Network.

Model 2. Use of Bitcoin (with the Lightning Network) as “rails”

In terms of transaction costs, layer 2 solutions such as Lightning Network can help a great deal as they essentially bring those transaction costs down to near-zero (at least for now) — allowing for highly competitive rates when compared to traditional remittance services. One company championing this model is Strike: with El Salvador as its first testing ground. In fact, that “testing ground” has ramped up to full-scale. Not long after catching the positive attention of President Nayib Bukele, a new bill passed into law. This so-called “Bitcoin Law” turned Bitcoin into legal tender and went into effect in September 2021.

In El Salvador, Bitcoin’s legal tender status exempts its users from “taxable events” for sending, receiving, selling, etc. But even as Strike launches in more and more countries that do consider cryptocurrency transactions as taxable events, there will likely be none required. This is because the sending person pays in fiat currency, and the recipient also receives fiat. Neither touch Bitcoin. Strike handles the Bitcoin behind the scenes.

Thus far, the Strike model (Bitcoin + Lightning) proves itself as the most promising for Bitcoin/Blockchain-based remittance solutions — so far.

Model 3. Use of stablecoins such as USDC and USDT (Tether) without Bitcoin

This model merely involves multi-token cryptocurrency wallets and those wallet providers marketing their capability of sending and receiving fiat-backed stablecoins as a “remittance.” Two such examples are Coins.ph and Crypterium — both using USDC.

Of course, this is not remittance in the traditional sense (which usually involves actual paper or digital fiat currency — not some privately issued asset offering redeemability for digital fiat), but it amounts to what I think of as a “do-it-yourself [DIY] remittance.” (The recipient would have difficulty in spending stablecoins for goods and services in the market in which they live. 7-Eleven does not want Tether as payment in exchange for a bag of corn chips). So the “do-it-yourself” part comes stablecoin recipient goes to a cryptocurrency exchange that is capable of allowing the person to sell the stablecoins and “cash out” for fiat currency — either to a bank account or even possibly in cash (depending on local laws and tradition of a country). There could alternatively be a paper money “cash out” option through a financial intermediary of some sort, but ultimately, the process involves the “stablecoin remittance” recipient having to go through some process of selling the stablecoins they received in exchange for the fiat currency that merchants in their local area will accept as payment.

Note also that since the stablecoin sender likely buys the stablecoins from an exchange, and since the stablecoin recipient likely sells them on an exchange, fees are likely to be charged for both parties on both ends. One must consider this when calculating this model’s costs as compared to traditional remittance services.

Model 4. Use of stablecoins such as USDC and USDT (Tether) with Bitcoin over Lightning

There is a hybrid model that was initially used by Strike before the company dropped its use of USDT (now using Bitcoin over Lightning without stablecoins instead) due to concern about this stablecoin’s USD backing. This model was summarized by Coindesk as follows:

“Strike would debit the bank account of a sender in the U.S. for, say, $1,000; convert it to bitcoin; send that BTC to the company’s Central American infrastructure; and then convert it to USDT, credited to the recipient’s account… If users didn’t want to hold USDT, they could convert it to BTC through Strike and, if desired, cash it out for dollar bills at a local bitcoin ATM.”