Many might wonder where the Fed inflation target of 2% comes from. This article delves into the origin of that target, and sheds light on how this strategy came about.

Jerome Powell

On Sunday, February 1st, 2024, Jerome Powell was interview by 60 Minutes. Countless headlines were made, most of Bitcoin Twitter noticed him skating through the US Debt and how the US government is “on an unsustainable fiscal path. And that just means that the debt is growing faster than the economy.”

I will save the conversation about the US Debt for another day, perhaps when it crosses $35 trillion which some expect to happen by September of this year. Instead I want to focus on another key takeaway from Powell’s interview and countless FOMC press conferences: 2% inflation.

Where did this number come from? Surely the economists in charge of the world’s (and history’s) largest economy contrived this figure from a mathematical formula that is well above my level of understanding.

Unexpected Role of New Zealand

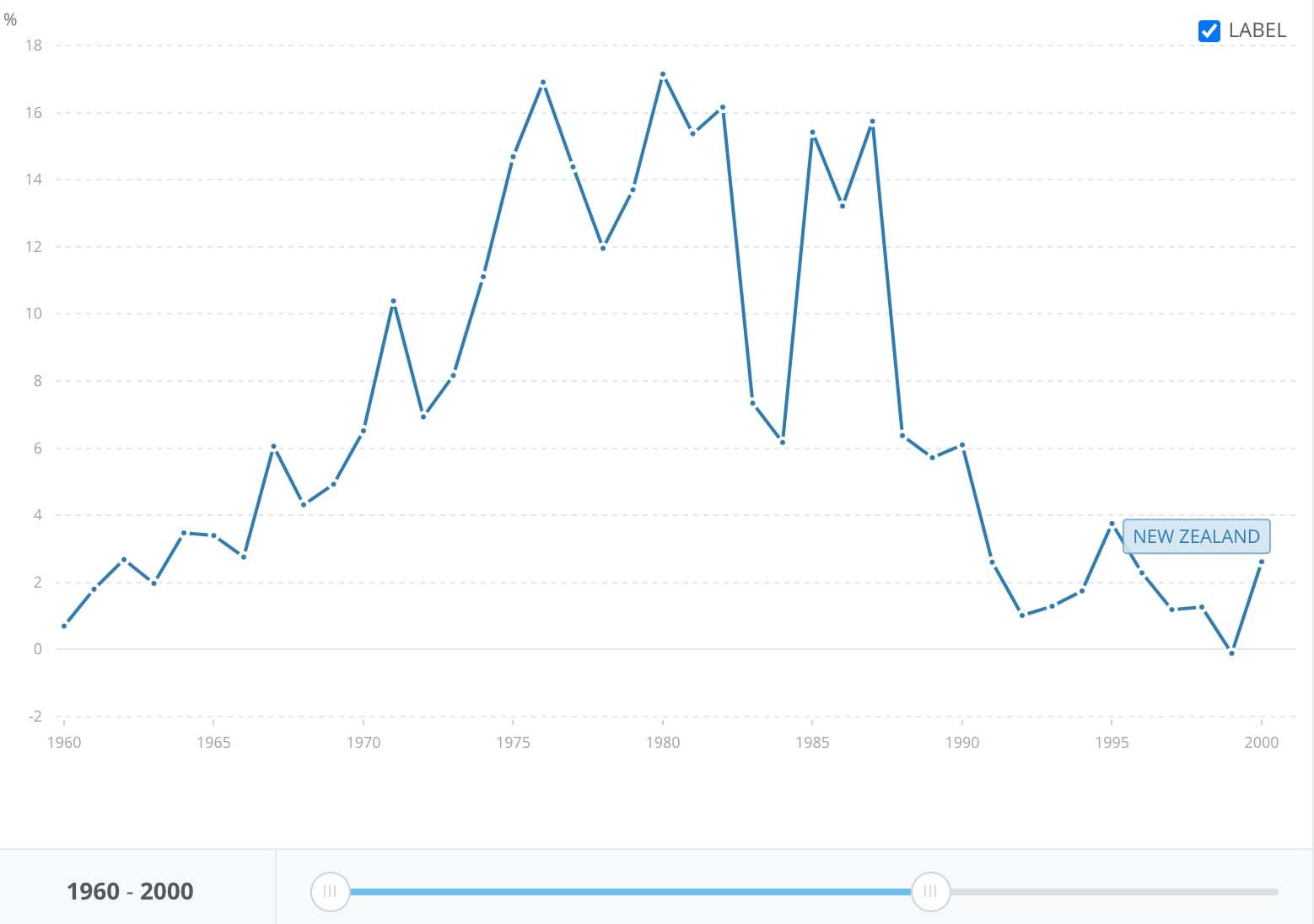

Sadly, this notion is grossly mistaken. In fact, it could not be further from the truth: the number it seems was chosen at random, not even by American economists, but voted on hastily by the New Zealand Parliament right before they broke from Christmas in 1989. Their logic, other than rushing home to spend time with their loved ones during the holiday, was to put the egregious level of inflation from the 70’s and 80’s behind them (see chart below).

Let’s not just leave things to wander off like a sheep into the paddock, especially not when it comes down to the whims and calculations of our central bankers. The very folks we trusted with the reins of our financial stability have shown, over the past two decades, that certainty is as elusive as a cloud’s shadow over the rolling hills.

David Caygill, the finance minister of New Zealand back in the day, remarked quite candidly that their real goal wasn’t about pinning down inflation but rather ensuring the Central Bank could stand tall, independent of the political winds. Amidst some murmurs that targeting a specific number might boost employment figures, the loudest critics were, quite conveniently, out of commission, hospitalized.

And so, with the ink drying on the legislation, a target was needed. An offhand comment in an interview suggested zero to one percent, a figure so casually tossed into the air you’d think it was meant to mingle with the clouds. Don Brash, then the captain of the central bank’s ship, let slip that this initial figure was more a kite flown to gauge public sentiment than a hard anchor.

Yet, from this wisp of thought, they nudged it up to 2%—a bit more elbow room, as if deciding how much pasture a sheep needs to graze. In this twist, it turns out the journey from whimsical remark to legislative anchor was less about meticulous calculation and more a dart thrown at a board, showing that the path to this decision was as serendipitous as finding a four-leaf clover in the vast fields of economic policy.

But how did this island, which currently has a GDP 22 times less than that of the United States, come to influence such a paramount decision that would shape the rest of the world from then on out?

Occam’s razor: the politicians hit the campaign trail. Mr. Brash did a bit of a global campaigning, describing New Zealand’s success to his fellow central bankers at a conference in Jackson Hole, WY. — and to anyone else who would listen. Canada, Great Britain, and Sweden were quick to adopt this new 2% benchmark. But the US dragged its feet as the political apparatus tends to do stateside (a rare blessing that was squandered).

Enter Janet Yellen

Paul Volker and the Fed Chairman at the time, Alan Greenspan, believed the inflation target should be as close to zero as possible, yet there was a young Fed governor who believed the target should actually be above 2%. Her name was Janet Yellen.

“To my mind the most important argument for some low inflation rate is the ‘greasing-the-wheels argument,’” Ms. Yellen said in a closed-door meeting of Fed policy makers in July 1996. Ms. Yellen’s argument — that some inflation would help grease the economy’s wheels and give central banks more flexibility to respond to a downturn — prevailed, in the sense that 2 percent became the widespread target of global central banks.

But what does 2% inflation look like over a long enough time horizon, if this is the mark that is kept consistently? The Rule of 72 dictates that is you divide the interest rate (2% in this case) by 72, you will see how long it takes for an investment to double.

This logic would lead prices to double every 36 years. We have seen prices more than double in the 28 years since this policy was adopted in the US, but I want to share a personal story of watching 2% inflation impact a cup of coffee.

Fed Inflation Target in Action

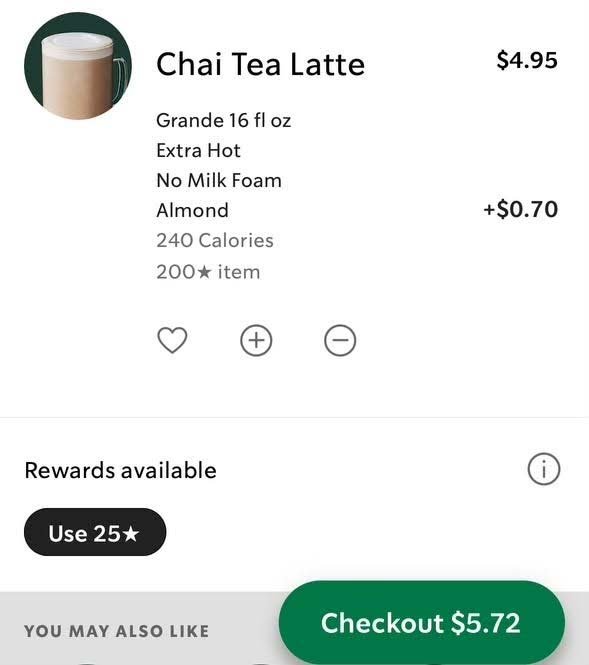

Back in 2002, my mom would give me $3.25 to buy her the same order from Starbucks: grande chai latte, extra hot, no foam, almond milk. This most recent Christmas Eve, she asked me to pick up her order before we met up for Christmas Eve dinner. While somewhat surprising (although not entirely, given the state of inflation), the drink cost $5.72.

I remember the first time the price went up in 2003 and she was baffled that she had to give me an extra dime to complete her order, but 22 years (technically 21 years at the time of the order), we don’t bat an eye to this. So while we drove to dinner I decided to do a little math using the compounding interest formula (C.I.= P*(1+r/n)^nt): 3.25*(1+ 0.02/1)^22 = $5.02. $0.70 less than the current cost of the chai latte, but much closer in price than simply assuming the price jumped from $3.25 to $5.72.

I do not want to discredit the poor policy decisions that have led us to our current inflation crisis. We are seeing prices increase month over month (sometimes week over week). I’ve seen some small businesses stop listing their menu prices on boards because they have already had to pay to change their menu boards and have instead opted to handwrite new prices when they make that decision.

But it would be naive to ignore this ludicrous policy decision that has compounded into what we are dealing with today. Something to consider next time we hear policy makers talk about the arbitrary 2% inflation mark as though it was well thought out.