This article was originally published by Niko Jilch on FixTheMoney.net

The year is 2050. Cash has largely disappeared from everyday life. Anyone caught with any form of paper money is considered suspicious. Drugs? Money laundering? Sabotage? Cash is dirty. The currency is digital now. But: Our digital payment transactions have long been fully monitored. This has given economists and central bankers completely new possibilities. As well as the police.

After the European blackout of 2035, the EU rolled out the digital euro at lightning speed. Sure, at first glance, it’s counterintuitive to respond to a blackout by introducing a digital currency. Cash was king in the blackout, after all. But when every European was offered €500 in “crisis bonus” fresh from the European Central Bank‘s digital money press, doubts quickly evaporated. After a few days, hundreds of millions had a digital account directly with the ECB.

There were many teething problems. But 15 years later, the digital euro is a completely normal thing that is not questioned. Bitcoin still dominates the black market today. And it is rumored that the rich and powerful have long used digital accounts on the blockchain to circumvent their own rules. But these are just rumors. The masses don’t have time for illegal currencies. They have to go to work and pay taxes. And play by the rules. Otherwise life will quickly become expensive.

Individual tax rates have long been set according to consumption patterns. This is what the “global agreement on establishing fairness and ecology in the tax system,” the GLOBFAIR, introduced. Since it was adopted in 2034, there are no more loopholes. Of course, the promise to finally counter climate change this way was not kept. But the system has remained regardless. Shopping behavior, social media, the workplace: those who behave the “right” way are rewarded. Those who don’t are punished. The only problem is that the definition of what is right — and what is wrong — is different everywhere.

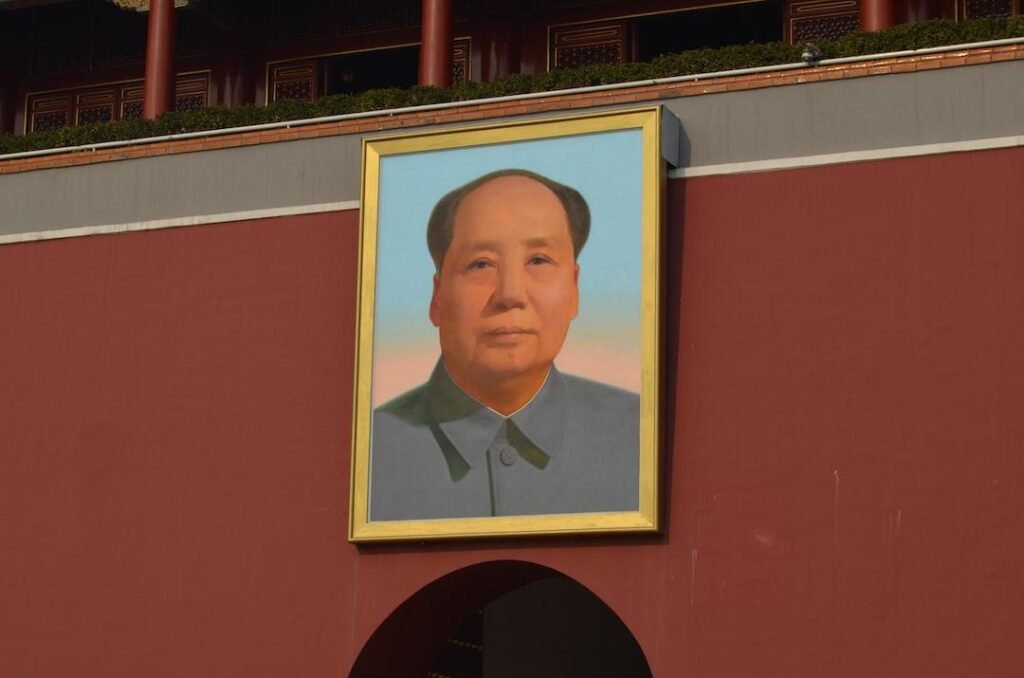

China has led the way. When the digital yuan was presented to the world in 2022, people in Europe and the USA were still relaxed. But when the Chinese diaspora began to use the app with Mao’s face in the West, central bankers in Washington and Frankfurt became nervous. Digital plans for the dollar and euro were brought forward. Central bankers and politicians traveled to Beijing for inspiration. The new technical possibilities were too tempting. It was the end of anonymity. A new age of electronic surveillance dawned.

An unrealistic scenario? A polemical exaggeration? Hopefully. But unfortunately not necessarily. It is well known that China wants to introduce its digital yuan as early as 2022 — at the Winter Olympics in Beijing. The giant communist empire also makes no secret of the fact that digital money is to be part of its surveillance state. Anyone who uses cash already makes himself suspicious. And anyone who buys the wrong thing electronically or otherwise attracts attention in a way that displeases the regime will end up on the blacklist. In the Western media, this is called a “social credit score.”

Related reading : Financial Tyranny Index Highlights The Need For Bitcoin

It sounds harmless, but it’s not. China monitors its citizens at every turn. Not only payment transactions are screened and evaluated, but also behavior on social media and elsewhere on the Internet. Private chats? Not a chance. In China, you never know whether a message has been received. Anyone who uses the wrong terms is automatically deleted. The digital yuan closes one of the last loopholes: Cash — and the use of “private” apps like “We Chat Pay” and “Alipay.” The market has made China great. It has done its duty now. It can go.

The digital yuan is a tool that would have suited the secret service of the former communist East of Germany just fine. It is a surveillance currency. Your account is with the Stasi.

There is also no escape. The Internet is under control, protected by the “great firewall.” Bitcoin miners have been thrown out of the country, crypto exchanges have been closed. Tech founders like Jack Ma have had their influence severely curtailed by the regime. Xi Jingping probably wants to establish himself as ruler for life. He is tightening the reins everywhere and centralizing power in Beijing.

And it is there, of all places, that the German Bundesbank is drawing inspiration for its European plans for a digital currency. This is what happened in September 2021 at a Zoom conference among central bankers. “E-yuan and digital euro: Germany wants to learn from China,” reported the Frankfurter Allgemeine. What exactly can be learned from an undemocratic system of total surveillance, however, is not specifically spelled out in the article.

But still. Jens Weidmann, then head of the Bundesbank, lays it down: the digital euro will “not be a jack of all trades.” What does he mean by that? Weidmann cleverly reveals the dirty little secret: “A digital euro would not be as anonymous as cash.” Yes, privacy would have to be preserved. Somehow. By lip service. But if the worst came to the worst, the authorities would already have access. On suspicion. That cannot be prevented.

Weidmann is thus putting his finger directly in the wound. The ECB has already conducted a survey among Europeans and found that by far the most important thing to people in Europe is the protection of their privacy. In Germany, Austria, and southern Europe in particular, cash is still the most popular way to pay for purchases. The pandemic has weakened that, but it hasn’t changed it.

And that’s how “central bank digital currency” is being marketed. In short: CBDC, which already sounds like a secret service. The new money is to replace cash in the digital age. That is the central bankers’ first goal. The others are: Defense against foreign digital currencies (yuan, dollar); restriction of private payment service providers (Visa, Mastercard, Apple, PayPal); defense against bitcoin and prevention of all plans for private money from the hands of powerful corporations (Facebook, Amazon).

In addition, they want to go search of suspicious payment movements: Money laundering, terror, mafia. They want to design the system in such a way that the private banking sector is also happy. They also want to try out new economic concepts. Negative interest rates on private accounts? Unconditional basic income? Money with an expiration date? Controlling consumption? There would be hardly any limits to the economists’ ideas.

But there are so many questions: Who has to agree? The EU Commission? The national parliaments? Do we even need to change the EU treaties? Referendums?

Related reading : Iranian Parliament Warns Central Bank: CBDC Unlawful And Unconstitutional, Must Be Halted

Everything depends on how the “digital euro” is designed in detail. There are hardly any answers yet. Only a rough timeline. In 2023, we should see a prototype. There will be no need for a blockchain like the one used by Bitcoin. Bitcoin is the decentralized alternative to beat — with the full power of the law and the central server architecture of the ECB. The digital euro will most likely be modeled after a European real-time payment system that already exists: TIPS. Target Instant Payment System.

And yes, apart from all the horror scenarios and surveillance fears: The digital Euro has to solve a concrete, real problem. It’s true that our money is already often digital in everyday life — but only cash is “central bank money” and only “central bank money” is also legal tender. So what would distinguish a digital euro from today’s? The signs with “cash only” would finally disappear from Vienna’s coffeehouses. Because the digital euro must be accepted.

What’s the point of all this if cash does exist? The ECB also firmly maintains that it does not want to abolish cash. It has just started the redesign of the euro banknotes. But the trend toward digital payment will be unstoppable. What is needed today are preparations for Day X, when not the state but the market and its participants decide by a majority that they no longer want to rely on paper money and coins. Then the central bank must offer an alternative for its central product. Otherwise, it would not be doing its job.

The issue of privacy can also be viewed in a differentiated way: Haven’t we long since been revealing ourselves to the U.S. tech giants on a daily basis? Don’t Visa, Mastercard, Google, and Apple know everything anyway? Yes, but — at least in theory — they still form a wall against the authorities. And we do it voluntarily.

So there needs to be a digital equivalent to cash. But without privacy. Agustín Carstens, the head of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), has already explained it in a video that caused a furor on the internet: Digital central bank money will “not be like cash,” Carstens said. Because the central bank will have “absolute control” over what happens to the money. Not very reassuring.

And Carstens is not just anyone. The BIS is a powerful financial organization that hardly anyone knows about. A sort of think tank for central banks, where thoughts about the future are spun. Founded after World War I to handle the payment of Germany’s war debts, the BIS has been adept at finding new tasks and staying relevant. Now it deals less with gold and more with computers.

But even once the exact design of the degree of surveillance in the digital euro has been clarified, things are not yet in the clear. We are rattling along at top speed into a world with competition between currencies and payment systems.

So it’s understandable if the ECB wants to protect its product, the euro, from the yuan, dollar, and bitcoin. But how will it ensure that the digital euro only reaches Europeans? Or do they want to engage in a global showdown anyway and also offer it to users in North or South America? The euro also thrives on its role as an international currency. Especially in unstable countries around the EU, it plays a role for the population — as cash. And with Montenegro, at least one country that is not even in the EU has introduced the euro as its national currency. Will the Montenegrins have access to the digital euro? It is unclear.

Bitcoin is the next problem. The cryptocurrency was created by its mysterious inventor Satoshi Nakamoto expressly to prevent a horror scenario like the one described at the beginning. To “carve out a piece of freedom” for the people. Bitcoin is already much closer to a true digital cash substitute than digital central bank currencies will ever be. It has established itself as a national currency in countries like El Salvador and at least as an investment asset in the wealthy West.

Millions are using bitcoin. Billions flow into it. And it’s built to withstand attacks and bans. Governments will not be able to stop Bitcoin — rather, the digitization of currencies will fuel its development. Only China has a chance to help itself with sheer force and electronic walls. But the democracies of the West are not in a position to do that.

And the banks? They are by no means happy. If everyone can get an account at the ECB, why do they need one at Raiffeisen or Santander? What role do commercial banks play in this new world? What about negative interest rates? If every European maintains his or her own account with the ECB, digital bank runs could occur within minutes, with people pulling their money out of a bank in a panic — because they heard news or rumors about the bank’s stability.

To prevent this, the ECB is considering a cap of 3,000 euros per account for the digital euro. Any holdings of digital euros above that would automatically be transferred to the current account. But again, an answer is followed by three questions: Will this cap be adjusted for inflation? Will corporate customers get higher limits? And what about in the event of a crisis, when a bank really falters and customers quite rightly want to flee under the protective umbrella of the central bank?

A well-designed digital euro could give Europe a competitive edge in the global market. After all, the ECB is considered the most “independent” of central banks since it is not answerable to just one state. Will that be enough to create trust among users? Or will they not care in the end, because digital money is needed in a digital world?

Washington does not yet have any answers to this question either. Unlike China and Europe, however, the issuers of the world currency apparently see little urgency. Jerome Powell, the head of the Federal Reserve, said that they are still examining the issue. Of course, the U.S. is also a leading nation in the digital world, and there will certainly be something like the digital dollar. But it is not yet clear whether this will have to come from the central bank at all. The U.S. has the deepest capital markets and, unlike China, is not afraid of capital flight. And they are observing an interesting process around Bitcoin.

In the crypto world, there are de facto two reserve currencies: Bitcoin, the oldest and largest cryptocurrency. And the dollar — in the form of so-called “stablecoins.” These are digital currencies that are pegged to the “real” dollar. These are issued by private companies — and they are enjoying tremendous popularity. Suddenly, billions of people in countries with poor, inflation-ridden currencies have access to dollars at lightning speed. Users don’t care much that they are derivatives. Thus, the new world of blockchain is helping to establish the dollar as a reserve currency among a whole new generation of private users. What if such dollar coins are issued by banks to make them available to companies as well? Will the digital dollar end up coming not from the central bank at all but from the private sector?

At the start of 2022, there are still many more unanswered questions than there are answers when it comes to digital currencies. We only know four things: digitization cannot be stopped. This also affects our currencies. China is much further ahead than the West when it comes to digital money. But Beijing must not serve as a role model — but as a cautionary example.

This article was translated from German — and slightly adapted/edited. It was originally published in January 2022 in the Austrian magazine Pragmaticus. You can read the German version here.