This article was originally published by Dominic Frisby on Moneyweek.

An 18-year cycle in the UK property market says house prices will crash in 2026. Dominic Frisby explains how it works.

It’s a national religion for some, heresy for others – today we look at house prices.

But we do not consider property through the window of the estate agent’s, but rather through the prism of an 18-year cycle, one that was brought to public attention by economist Fred Harrison is his cult classic Boom Bust: House Prices, Banking and the Depression of 2010.

He published it in 2005 so, if you’re into forecasting, that’s some title.

Cycles are often what you want them to be

Before we start, let me issue my usual disclaimer on cycles.

Cycles exist everywhere: the seasons of the year, night and day, the life cycles of plants and animals. They exist within our own bodies in the form of circadian rhythms. They exist, sort of, in markets too – there are good times and bad times, bull markets and bear markets, four-year presidential cycles, supercycles and more.

Mining companies, in particular, go through clear cycles – perhaps phases is a better word – from exploration and discovery, through development and mine building, to actual production.

I’m a keen observer of hype cycles. How much of this story is known? How much more hype is left in the tin? Or is this story now tired?

And cycles can make for good copy – Kondratiev made his name peddling them. We like reading about them because they bring a veneer of certainty where there is, in fact, often none.

But as that last point alludes to, cycles – especially in markets – are also arbitrary, random and uncertain. It’s easy for an academic to look back at history, find a pattern and declare it a cycle. When real life doesn’t fit the model, you’ll hear something like: “Well, the war upset the cycle”, or “they printed loads of money, so the cycle didn’t work out” or whatever. Cycles in markets are not fixed and predictable in the same way as the days and weeks of the year.

You get the point. There is a certain amount of salt to pinch when it comes to cycles. Nevertheless they are useful instruments. I know some who swear by them, especially Harrison’s, whose book was clearly brilliant in its forecast.

I remember thinking in 2005: “This market is nuts. It has to crash”. Many felt the same way, including many of the brightest minds in the City. A whole website – housepricecrash.co.uk – sprung up around the theme. Many of us were certain the game was about to end.

Then I stumbled across this brilliantly prophetic article by Harrison in MoneyWeek saying, “No, we are a couple or three years from the top”. He was right.

After last week’s missive on house prices versus gold, I was thinking about our distorted property market and the spectre of rising interest rates. The thought occurred to me that we must be close to Harrison’s next peak. Lo and behold, Merryn interviewed him in the latest MoneyWeek podcast.

Harrison’s short answer is that 2026 will see the top of the market. We have another three years, in other words.

A quick guide to the 18-year property cycle

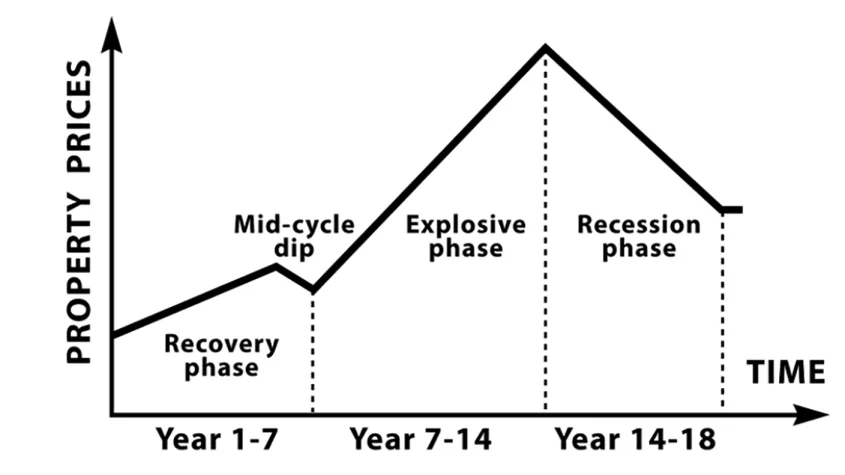

Let me quickly explain how his thinking works. His idea – and it is more about land prices than it is house prices, though the two tend to rise and fall together – is that property tends to see 14 years of price growth, followed by four years of decline.

Broken down an 18-year cycle might something like this:

Harrison says he can follow prices back some 200 years to find this clear 18-year cycle at play.

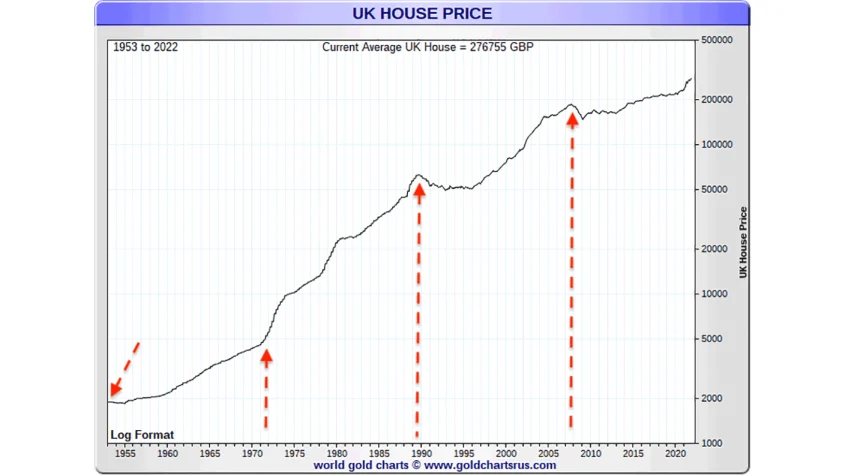

I don’t have all the data to cross check back that far, but I do have the data going back to 1951 (care of Nationwide), so let us at least check that.

Before World War II, property was not the overpriced monster it is today. Home ownership was lower (sub-25% most of the time – most people rented from private landlords) and mortgages hardly existed (they only really reared their heads in the 1930s), so the cycle, even if visible, would not have been as pronounced as it is in today’s debt-ridden fiat era.

The top of the last cycle (in the UK) actually came in the third quarter of 2007. The average house price then fell from £183,000 to £149,000 in the first quarter of 2009. It would be 2012 before the market properly got going again.

There was definitely a buying window during that 2009 to 2012 period, but prices, especially in London, did not fall by anything as much as many buyers were hoping. That’s mostly because there were few forced sellers, because interest rates were slashed. Had there been, then house prices would have come down by a lot more.

They fell by a lot more than 18% if you were a foreigner, however, as the pound lost a good 30% in the foreign exchange markets (measured mostly against the US dollar).

Go back 18 years and you have the crash of 1989-1994. Prices peaked in the third quarter of 1989 at £63,000, before falling to £51,000. Things got going again in the mid-to-late 1990s. The pound lost a lot of value in the forex markets then too.

Going back 18 years further takes us to 1971-1972. The 1970s were a horrible decade economically, but housing was not the worst place to be. Houses were a better inflation hedge than cash. And between 1970 and 1973 house prices actually doubled.

So we are going to declare that Harrison’s cycle did not work here.

However go back another 18 years to the early 1950s, and house prices did see declines, before the market took off in the second half of the decade and into the 1960s.

Here are UK house prices since 1951, with the cycle peaks marked by red arrows.

Going back further, I guess World War II upset the cycle. The recession of the early 1920s hurt house prices, then from 1926 to 1939 house prices rose a little, but by so little the market would be better described as flat. They went from £619 to £659.

Six hundred quid for a house! How money has been debased. It’s £274,000 now.

House price crash 2026? It could happen

All in all I’m going to give the cycle an A-minus. It is not perfect, but, like many cycles, it is a useful guide.

And a scenario of higher prices going into 2025-2026, followed by a slump, is something I can very much envisage.

So if you’re looking to buy, start getting your finances in place now. If the slump is anything like 2008, you’ll have to move quickly. If it’s like 1990-1995 you’ll have plenty of time.

I’ll be re-evaluating in 2025, but my own experience when it comes to buying your own home (investing in real estate is different) is that you have to move when the time is right for you, to the place that best fits your circumstances.

Trying to second guess the market can lead to unhappy outcomes. House prices only ever go up! And if they do go down, they won’t come down as much as you want them to.

And one final tip – period property keeps its value better than new build.

Make sure you listen to the podcast!

Dominic’s film, Adam Smith: Father of the Fringe, about the unlikely influence of the father of economics on the greatest arts festival in the world is now available to watch on YouTube.